It is 7:30 in the morning. I couldn’t fall asleep and now the next day is officially here. The “next” day is now today. Despite not having slept, I feel excited and alive. It’s a new autumn day, there is coffee, and there are books.

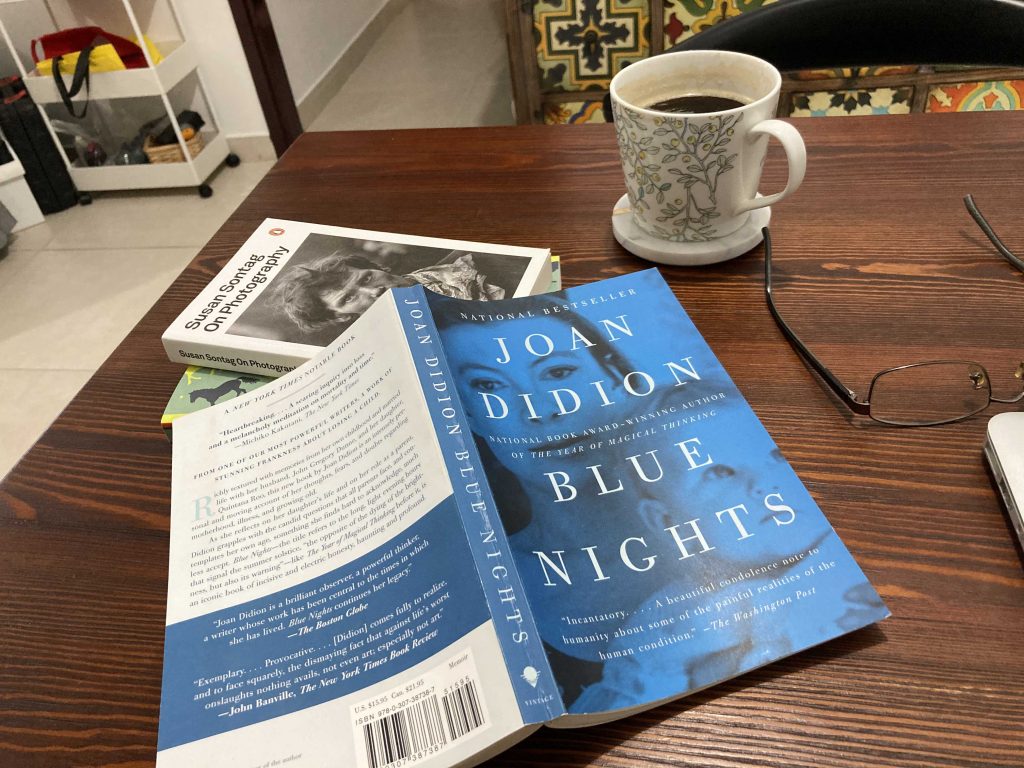

I’ve been feeling unwell for the past couple days. Nothing serious, it’s probably just a mild flu. But why wasn’t I able to fall asleep? I felt tired before bed. Was it the irritating manuscript I had to review? Was it the phone conversation I had–too late in the evening and too upsetting–that took away my ability to fall asleep? Was it reading from Joan Didion’s Blue Nights?

Don’t read anything of high quality before reviewing an academic manuscript. Don’t read Didion right before fulfilling your duties as a peer reviewer. I must tell myself. Maybe a post-it note placed somewhere visible on the bookshelves. The contrast between high-quality text and soulless academic manuscripts makes the latter even less bearable. Your fragile optimism, violated by the careless pseudo-arguments of an unskilled “scholar,” who has written to publish, to keep a job, to gain or maintain status,… who, of course, has all the degrees, your fragile optimism will grow back (if at all) very slowly.

I tried my best to be polite in my brief review, and I think I somewhat succeeded. This year, due to COVID19, I’ve had to [peer] review about 20 manuscripts for various journals. I think I will take a break for the rest of the year. That should give me enough time, let’s hope, for the recovery of optimism.

Compared to the reviewing, the phone call affected me more. I cannot write about that. I couldn’t write about it even if I wanted to. And I don’t want to.

After the phone call was over, I went and looked at myself in the bathroom mirror, noticing the white facial hair, especially on the left side of my face. I felt old. And exhausted. There is something about white facial hair that makes it a more forceful, and a more undeniable, sign of aging compared to the white hair on one’s head.

Then I came back into the living room and shared the summary of the conversation with my wife. I passed the story through a “funny filter” and we both laughed. But the funny filter failed to convince me, because I still had the unfiltered version of it.

Somewhat related to this mood, I’ve been working on a short piece of writing, which is currently titled, “Why Are You Not More Cheerful?”, in a style similar to “Learning To Pray,” which you might have noticed. In fact, now that I think of it, I see how it is a follow-up to “Learning To Pray.” I would’ve been working on that, instead of this, if I had a normal sleep last night. And you would’ve been reading, “Why Are You Not More Cheerful?” instead of this post.

Before I close, let me share a few lines from what I have been reading by the wonderful Joan Didion. It’s about aging, fragility, one’s presence in a shared reality, and one’s self-awareness of all these.

I hear a new tone when acquaintances ask how I am, a tone I have not before noticed and find increasingly distressing, even humiliating: these acquaintances seem as they ask impatient, half concerned, half querulous, as if no longer interested in the answer.

— Joan Didion (Blue Nights)

As if all too aware that the answer will be a complaint.

I determine to speak, if asked how I am, only positively.

I frame the cheerful response.

What I believe to be the cheerful response as I frame it emerges, as I hear it, more in the nature of a whine.

It is 10 PM now and I just finished reading Blue Nights. I went back and re-read a few passages from parts of the book, especially parts that I have underlined. Then I re-read the very first two pages, and in those two pages I felt the entire book, in condensed form. Didion writes, “Blue nights are the opposite of the dying of the brightness…” Later in the book, she explicates this sentiment, “When we talk about mortality we are talking about our children.” Blue nights offer us something so pleasant, so promising, that we almost inevitably forget the passage of time.

We let the blue nights transform into an illusion of something more, something permanent, something beyond nature and reality. But that very tendency might be something–a part of us–we should accept. It might be an inescapable part of our nature, as inescapable as the initial seeing and feeling of beauty (of the blue nights), to see more in it, to want to see more in it, to see permanence, and to demand more from reality.