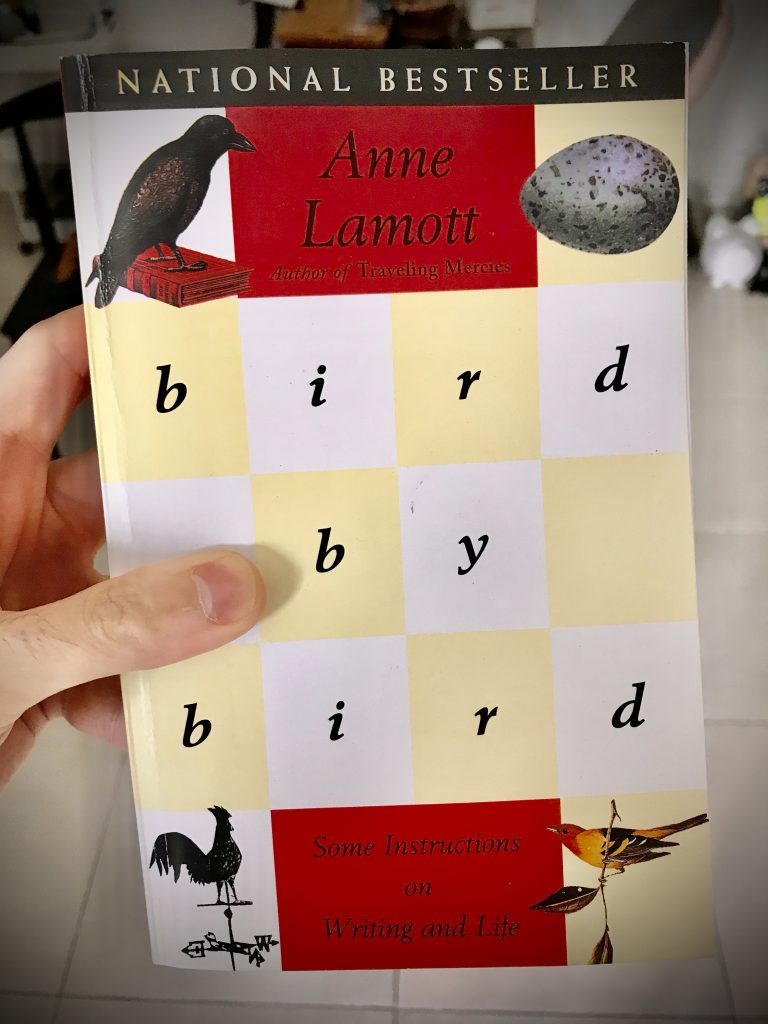

In a recent trip to the nearby bookstore, I bought two books. One of them is Terry Eagleton’s How to Read Literature and the other is Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life. I just decided to right-click and to add “Lamott” to my browser’s dictionary, not just because I was irritated to see it underlined as a possible typo, but also because of how much I loved her and her book. Even if I never write her name again, I want her name to be part of my (browser’s) dictionary.

I loved reading this wonderful book and my love for the book extended to my love for her, the author, for having written such a book. The book is about writing, but writing seems to become something else along the way: An excuse to communicate about more important topics. In some ways, this is similar to how people use “coffee” when they invite someone on a date. We want to love and be loved, but it is bad manners–not to mention risky–to talk about that early on, so we use “coffee” instead. Coffee plays the role of an excuse quite well, no matter how much some of us enjoy coffee qua coffee. Coffee qua date is something else. At the same time, no matter how poorly the date goes, you can at least enjoy the coffee. The coffee itself, coffee qua coffee, taken out of (its first) context (and viewed from within different contexts), as a little celebration, as a reminder of your intact health that allows for coffee drinking, and as a reminder of your persistent faith in love and taking chances.

Questions about writing, at least in parts of Bird by Bird, take the role of coffee on the first date. The date is related to the coffee, though it isn’t. The date is enabled, expressed, and materialized by the coffee. Coffee connects us or initiates our connections. In a similar way, while we read Lamott’s reflections on writing, writing fades into the background and we see her. We see her humanity and compassion. We see her insistence on celebrating, laughing about, and writing about our flaws, our misguided longings, our stubborn insistence on seeking solutions in wrong places. All that can be guided gently with, among other things, writing.

We write to learn, to practice commitment, to embody discipline, to discover and show self-compassion, to be free, to connect to each other, to communicate, to love, to make each other laugh, and to keep alive the mysteries of being in the universe.

Let me go back, once again briefly, to the comparison between writing and coffee. Enjoying and appreciating coffee, paying attention to coffee (and not all our other worries), not demanding too much from coffee, are all parts of an art. The art of being present. Lamott writes beautifully about being present. About the innocence of presence, the openness and vulnerability of presence. She writes about being present as a writer. But being present as a writer requires first being present as a human being. Writing requires being–or moving in the direction of being–soulful.

I forgot to mention that after coming back from the bookstore I first began reading Eagleton’s book, and I enjoyed it. But after about 20 pages I put it down and moved to something else. When I finally picked up Lamott’s book, I couldn’t put it back down (Ok, I did put it down for a moment to write a quick note of excitement about the book to my friend, Gairan). Lamott writes so well, so lovingly, so generously. At no point she asks to be praised as the great teacher of creative writing, as the heroine of the book. There is no pretense. No salesmanship. No talking down to the reader.

The way she talks about her close friends (neurotic, wounded, broken, jealous, …) is similar to how she talks about herself, both full of understanding and compassion and even reverence. She shows masterfully how reverence, self-respect, and love cannot come from denying our limits (or telling ourselves that we’ll transcend them the moment we receive our well-deserved fame and fortunate). Reverence, instead, comes out of nurturing the right relationship with our limits and finding, among all the limits, an innocent core that truly deserves love.

[T]he acknowledgement that in the midst of ourselves there is still a good part that hasn’t been corrupted and destroyed, that we can tap into and reclaim, is most assuring.

That’s from p. 106. On the following page we read:

To be a good writer, you not only have to write a great deal but you have to come to care. You do not have to have a complicated moral philosophy. But a writer always tries, I think, to be a part of the solution, to understand a little about life and to pass this on.

The project of being a writer is inseparably tied to the project of being a person. At the center of this project lays self-compassion. Without self-compassion, Lamott tells us, writing well (about anything or anyone else) is impossible.

By the end of the book, the whole topic of writing is re-arranged and re-framed in our minds. We come to see writing as absolutely 100% about writing, separated from fame, fortune, or even being published. Writing is its own reward. When sufficiently cultivated as a domain within your life, it becomes an unending source of wonder and amazement, play and practice, patience and surprise, repetition and discovery. It would, therefore, be fair to say that, although writing is absolutely 100% about writing, it is at the same time an excuse. (Better: a medium, a method, a path). It is, and it isn’t, about the “coffee”. What matters the most (i.e., our slow, step-by-step, bird-by-bird movement toward being soulful) is enabled, expressed, materialized by what might present itself, at first, as an excuse.